Intro

We’re back. When we left this sample in part one, we had:

- Extracted files from the original .msi installer

- Dynamically analysed the obfuscated JavaScript file

- Spoofed anti-debugging call checks to drop the loader

- Got the loader to drop the final payload

After spending some time statically and dynamically analysing this sample, I was able to uncover both the C2 and the malware variant. TLDR; as expected, the malware family was Rhadamanthys (an infostealer). This blog will focus mostly on the immense number of anti-debugging checks in the “final payload”, as touched on briefly in pt1. Hope you enjoy!

Environment Setup

To help with live debugging with a dissassembler and debugger side by side, it is best to clear the DYNAMIC_BASE flag on the executable using a tool like SetDLLCharacteristics. This stops ASLR from randomising memory addresses when the malware runs, ensuring that memory addresses in static and dynamic tooling match (note: this action changes the file hash).

Static/Dynamic Setup - Ida and x64dbg

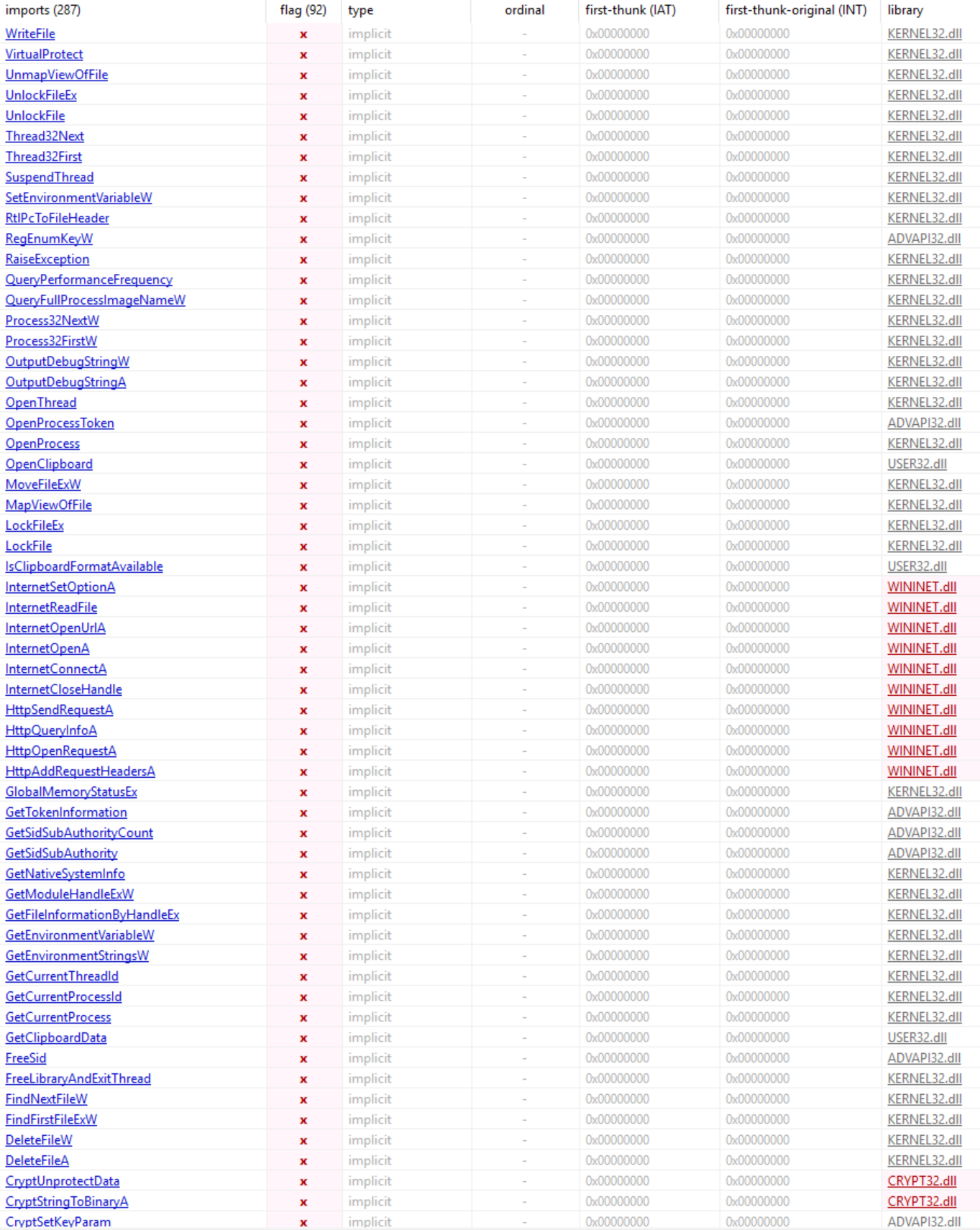

Quickly performing some static analysis on this binary, right off the bat we see quite a lot of interesting imports that appear to give away the potential functionality of this malware.

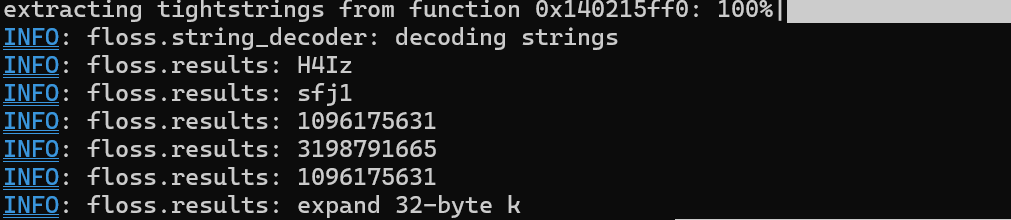

Running a tool like strings or floss is always a good next step to see what else might be within the binary. Unfortunately, with this sample it wasn’t as ez as strings == analysis done. It’s fairly common for malware to encrypt strings and dynamically resolve them at runtime. We only really see one useful or interesting string from the output of our tools, expand 32-byte k, which a quick google search will tell you is indicative of ChaCha20 usage.

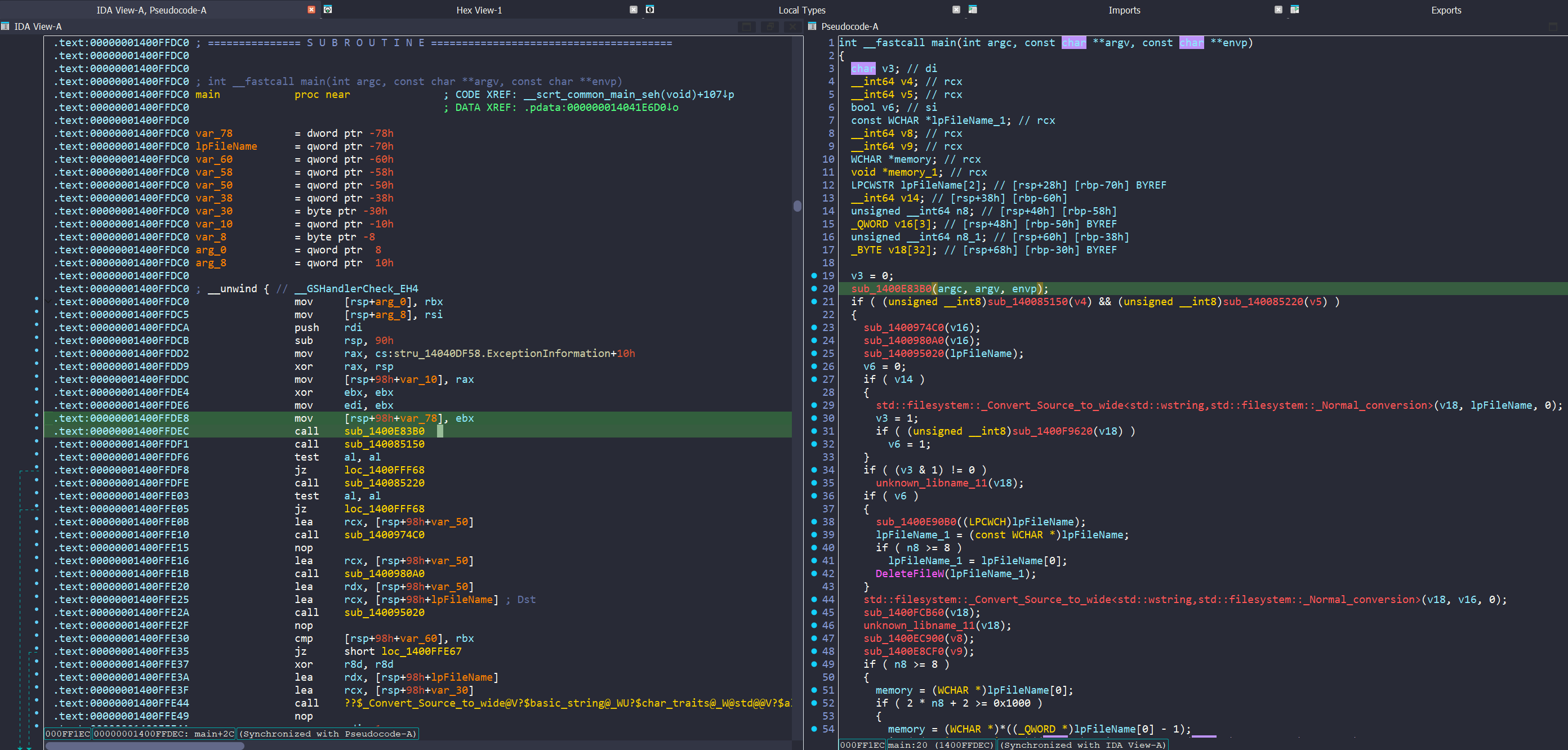

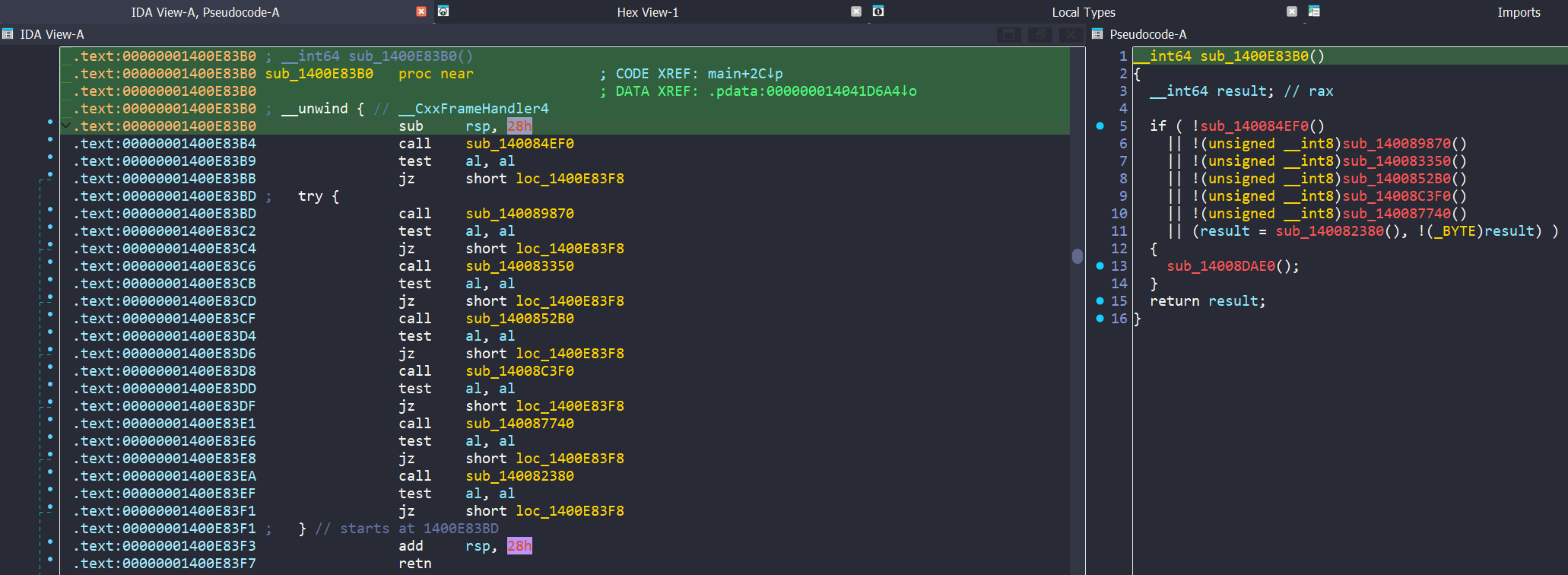

Opening the sample in Ida, after loading, it takes us to the main function. Syncing our view to the pseudocode, we note the first call at 00000001400FFDEC. Clicking into this function shows a series of checks, we can assume this based not only on the contents of each individual function, but by noting test al, al, which is checking the contents of the AL register after each function call.

Anti-Debug / Anti-VM Checks

Malware often employs anti-VM and anti-debugging techniques to frustrate analysts or prevent analysts from learning the inner workings of their malware. These techniques can range from basic to highly advanced. Often, sandboxes such as AnyRun or JoeSandbox will ’evade’ these checks and still return the core functionality of the malware. In this case, you’ll note that in VirusTotal there is no C2 in the ‘relations’ tab, and the linked sandbox runs show very low scores; this is because this sample employs quite a number of checks, as we are about to see. I won’t include all code for brevity’s sake, but will explain what each one does.

Check 1 - RAM and Processor Cores

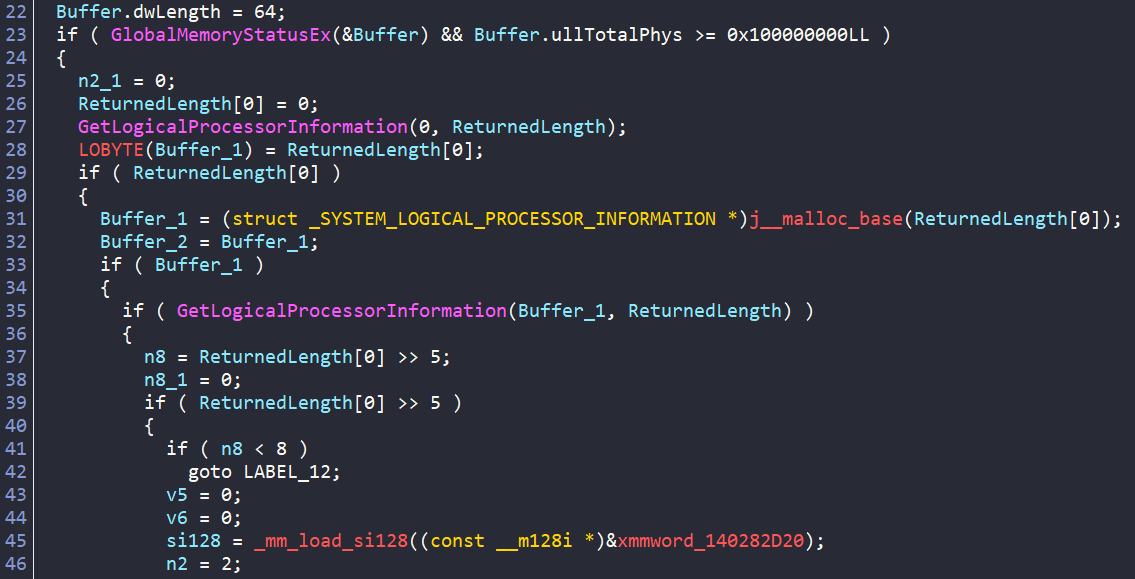

Starting with sub_140084EF0(), we see GlobalMemoryStatusEx and can infer the following is being checked:

- Total physical RAM - it calls

GlobalMemoryStatusExand checks ifullTotalPhys >= 0x100000000(aka at least 4 GB of RAM) - Number of physical processor packages - checks if > 2 processor cores

- Quits if < 4GB and < 2 Cores

Check 2 - Username Check

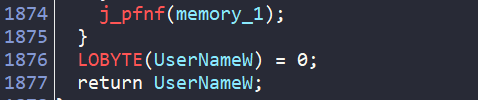

Next we have sub_140089870(), which shows ~1800 lines of pseudocode. This function:

- Uses TLS (Thread Local Storage) to hold a list of blocklisted usernames (john doe, johndoe, john, john-pc etc) and decrypts them via the decryption function at sub_140011FE0

- Gets the current Windows username via

GetUserNameWAPI - Converts it to lowercase

- Compares the current user to the blocklist

- Quits if there is a match

Check 3 - Computer Name Check

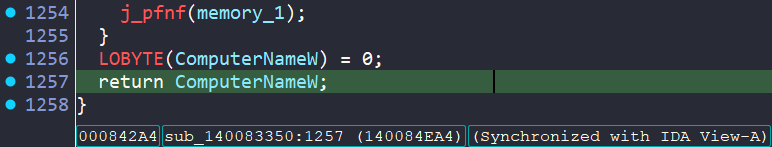

The function at sub_140083350() is similar to check 2. It:

- Contains a list of block listed hostnames in TLS

- Decrypts these and checks the current hostname against this list via a call to

ComputerNameW - Quits if there is a match

If I were to execute the malware on a dry run, I would make it this far, as my VM satisfies all these conditions. However, the next check killed my debugging.

Check 4 - Running Processes Check

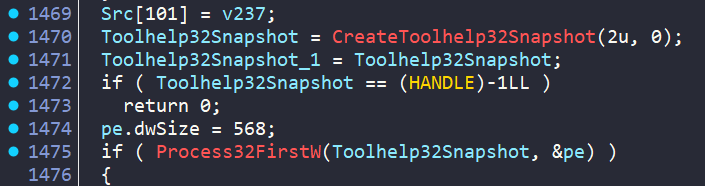

At sub_1400852B0(), we see a similar tactic of strings within TLS, however, if we scroll in this function we see a call to CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, commonly used to enumerate processes. This check:

- Contains a list of blocklisted processes commonly seen in malware analysis (ida, win64dbg, wireshark etc)

- Checks the running processes against that list

- Quits if any are matched

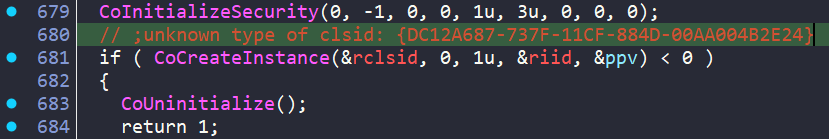

Check 5 - WMI Process Check

Then at sub_14008C3F0() we have ANOTHER process check, this time via WMI/COM. It:

- Initializes COM and connects to WMI (root\cimv2)

- Executes a WQL query

- Enumerates results, retrieving each process ‘Name’ property

- Lowercases it and compares against a blocklist of ~54 known analysis/debugging tool process names

- Returns 0 (match found = analyst environment detected) or 1 (clean)

Check 6 - Loaded DLL Check via WMI

The next check at sub_140087740() is almost functionally identical to check 5, however it is attempting to locate any loaded DLL’s that match a blocklist; looking for things like dbghelp.dll (debugger) or sbiedll.dll (Sandboxie) etc.

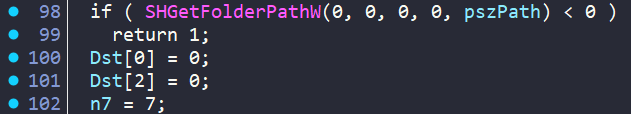

Check 7 - Filesystem Fingerprinting

FINALLY, coming in at check #7 is sub_140082380(), a filesystem checker. It enumerates through some of the filesystem looking to determine if this is a real machine or a sandbox with few files.

Actual Debugging

We now know that this malware has employed a range of anti-debugging and anti-analysis techniques, it is now our job to defeat these checks. There are multiple ways to do this; we could break on each test al, al instruction and manually set the AL register to equal 1 instead of 0 and then step through, however I prefer to just NOP the jump instructions. Setting a breakpoint at 00000001400E83BB (after the first check, I have 10GB RAM on this VM), and running the following commands:

memset 00000001400E83BB, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83C4, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83CD, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83D6, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83DF, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83E8, 90, 2

memset 00000001400E83F1, 90, 2

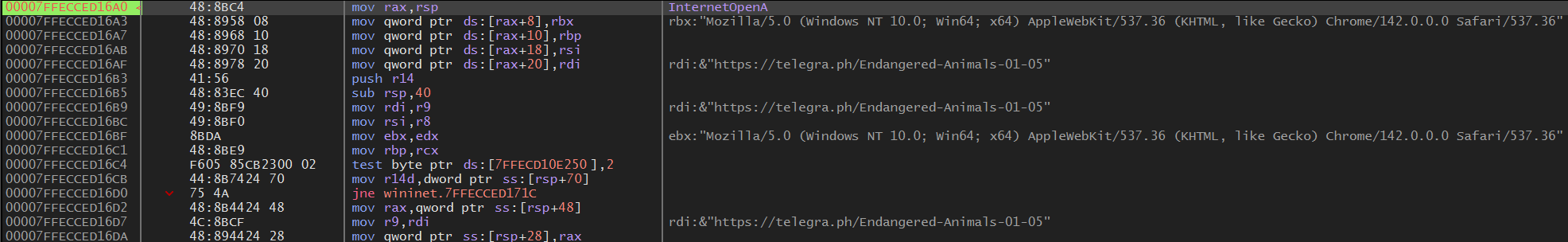

Each command replaces a jz short loc_1400E83F8 (2 bytes) with two NOP instructions, which means “do nothing and continue to the next instruction.” The conditional jump is effectively erased, so the code always falls through to the next anti-analysis check (and ultimately past all of them) regardless of what al contains. Before pressing F9 and continuing the debugging, I set a breakpoint on InternetOpenA.

Command and Control and Data Exfiltration

Once I now hit F9, I execute all the way to this call and if I hit F9 again a few times I catch the malware reaching out to the domain telegra[.]ph, this will require further analysis but is likely where the malware fetches the C2 address from:

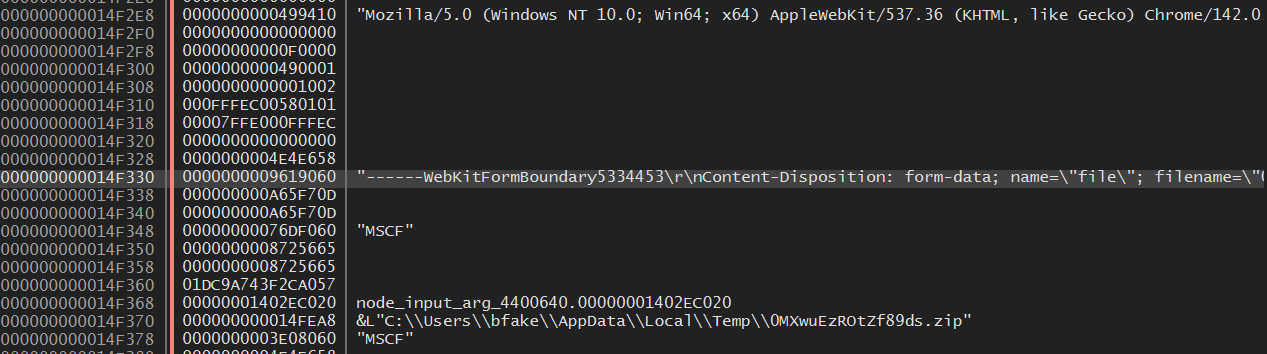

If we run until we hit the next breakpoint and look at the stack, we actually see a .zip file that was created on disk in %APPDATA%\Local\Temp. This contains all of the data that the TA is attempting to exfiltrate to their C2 server. Running a few more times we catch the domain inactivesophisticatedsolutions101[.]com, likely the C2 domain.

Looking in this file, we see 3 folders, 5 .txt files and a screenshot of the host:

- Browser (Autofills, Cookies, History)

- Files (VSCode user history, Desktop folders)

- Wallets (Chrome wallet extensions)

- Clipboard.txt (Copy of the clipboard buffer)

- Environment.txt (Environment variables)

- InstalledSoftware.txt (Installed software)

- ProcessList.txt (Running processes)

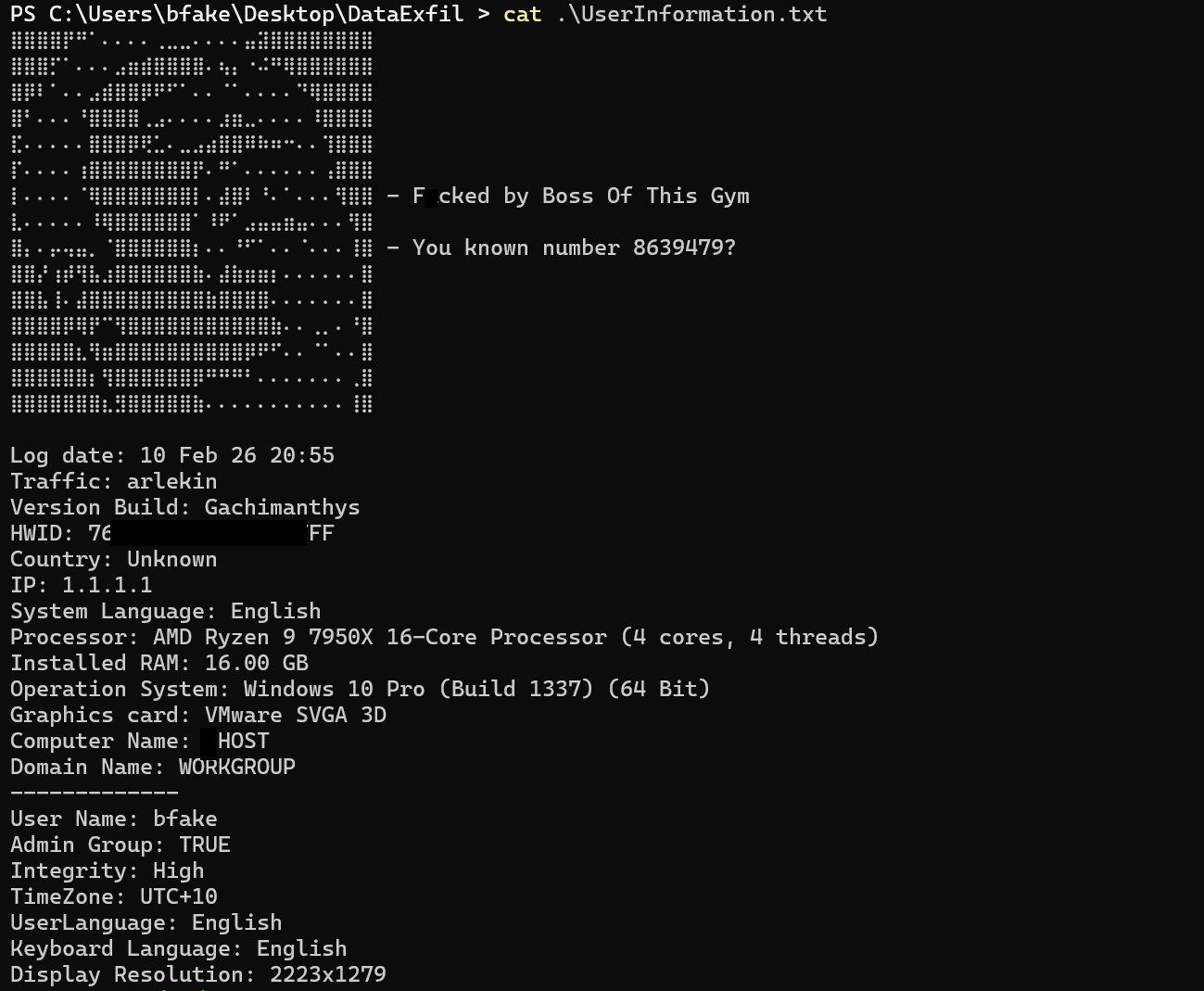

- UserInformation.txt (a bunch of hardware and tech info, plus a little easter egg!)

- Screenshot.jpg

UserInformation shows this build to be “Gachimanthys”.

Indicators

hxxps://inactivesophisticatedsolutions101[.]com

hxxps://telegra[.]ph/Endangered-Animals-01-05

hxxps://telegra[.]ph/Natural-Wonders-01-05